The Shape of The Sea

The Shape of the Sea

A portrait of life on islands at the edge of change, this project has been funded by the Revolutionary Storytellers 2025 grant from Photographers Without Borders and was featured by Transparency Maldives in the 6th edition of MAAHARA Digest.

The Maldives is often imagined as a paradise of white sand and turquoise seas. But for Maldivians, the reality is one of collapsing beaches, stagnating mangroves, and dying reefs - losses made worse by reclamation and dredging projects that prioritise development over sustainability. With little official monitoring or impact reporting, the changes are recorded instead in lived memory and community testimony.

In Ukulhas, dredging has altered wave patterns and accelerated erosion, stripping sand from the only non-tourist beach and causing shoreline buildings to collapse. Local surfer Ghazeel, just 20 and a new father, worries whether the island will remain habitable for his daughter. His friend Aiman fears he may never be able to raise a family here at all.

In Addu City, nearly 184 hectares of land have been reclaimed around Hithadhoo and Feydhoo. Promised as development, much of it lies barren, while shorelines, water flows, and reefs bear the cost. For Layaan, of youth-led Project ThimaaVeshi, the loss is deeply personal: her family home now floods with every rain, and her childhood picnic island has been swallowed by reclamation.

Across the atoll in Hulhumeedhoo, members of the local NGO Nalafehi Meedhoo mourn a beach lost to erosion and wetlands now under threat. Without formal governmental studies, these young protectors are left to monitor mangroves and lakes themselves, burdened with documenting a slow, quiet disappearance without support.

On Fuvahmulah, the erosion of the Thundi pebble beach has become alarmingly fast, destabilising the coast. A $19.5 million seawall project began in 2021, yet the trade-offs have been severe. In 2023, a barge grounding caused catastrophic reef damage near dive sites, devastating a reef known for its unusually high coral coverage. Local silversmith Shanu and dive guide Ricky describe not only vanishing sand and murky waters, but also the grief of watching a thriving ecosystem scarred.

For Maldivians, these are not distant environmental statistics, but an urgent loss of place, memory, and livelihood. With little official documentation to account for what is disappearing, young islanders have become the record-keepers, with the burden of evidence placed on them - to acknowledge their stories is to share the weight of witnessing the changing shape of the sea.

“I grew up with the ocean at my fingertips, but now the home I knew is being erased.”

A juvenile grey heron searches for food on an eroded beach, whilst trees struggle to keep their roots on the shoreline.

Ghazeel sketches out the erosion issues on the very sand that is eroding.

Ghazeel and his fellow surfers are struggling to maintain their routines with the changes to the waves.

“When I was younger, the sea was further away. Now, it is at our doors.”

“The word Thimaaveshi, which means ‘environment’ in Dhivehi (the Maldivian language), encompasses both the word for one’s natural surroundings and the word for oneself - indicating that one cannot exist without the other.”

Anoof, a member of Project ThimaaVeshi and a Hithadhoo local, surveys the bare, reclaimed sand.

“This used to all be the sea.”

"We don't recognise our home, where we grew up our entire lives, anymore."

“We used to go to this beach every single day after school. I really miss it.”

New geometry is being carved into the shores, by both nature and man.

Shiuma (left) and Sajaya (right) hope that there is still time to save their mangrove.

Aerial views of the mangrove show the stagnation of the mangrove, and the cause.

![“It’s all about developing to be like the Malé [the capital city of the Maldives], but people don’t realise the significance and importance of the wetlands to our ecosystems and environment, and the cost being paid.”](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5937fe0203596e024e7745d2/1759513529706-4NLAEILKP4L3RVBRH7KT/THESHAPEOFTHESEA2025_SOPHIANASIF-10.jpg)

“It’s all about developing to be like the Malé [the capital city of the Maldives], but people don’t realise the significance and importance of the wetlands to our ecosystems and environment, and the cost being paid.”

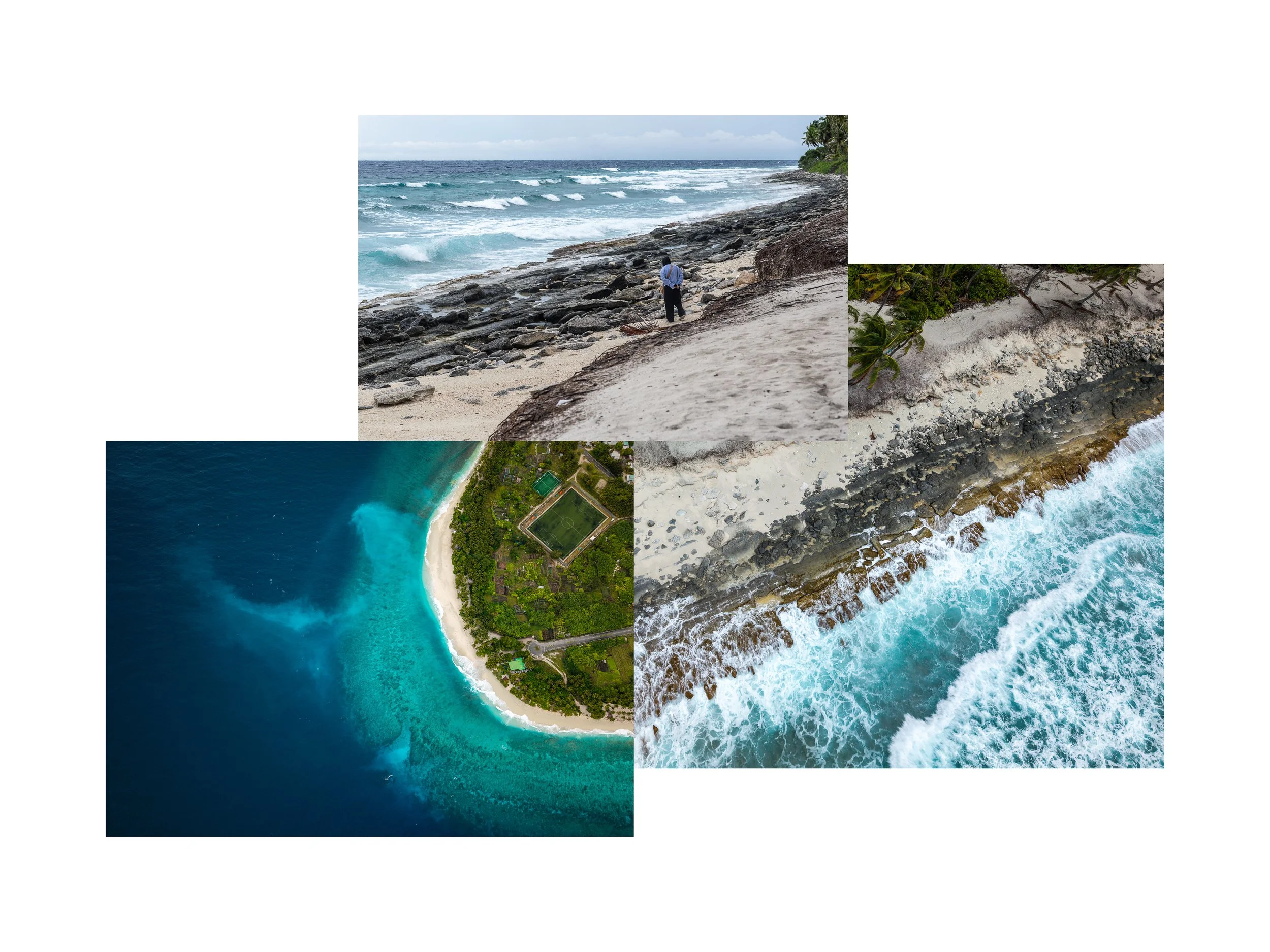

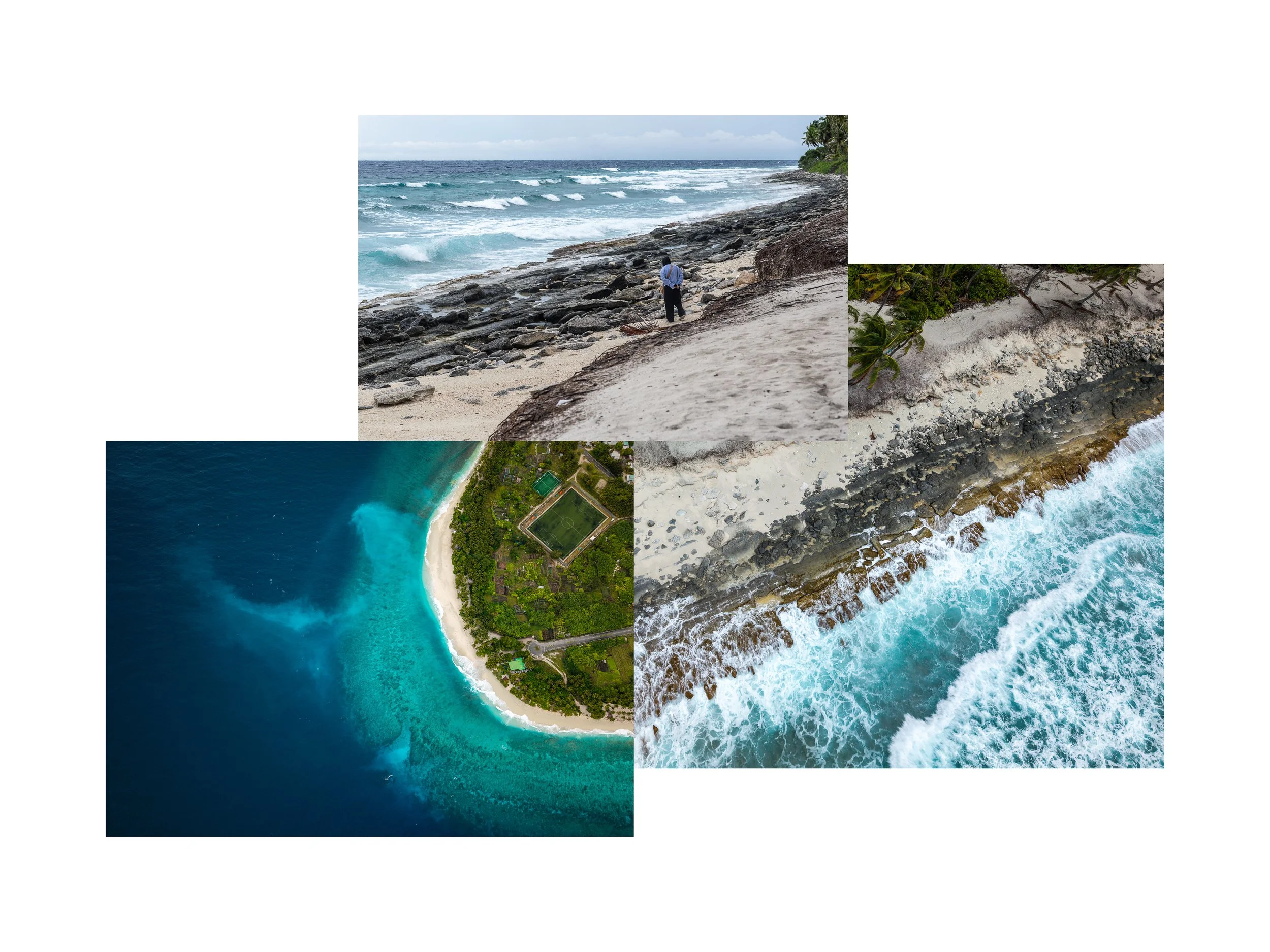

Shanu walks on the thundi at the top of this picture, and on the previous location of the thundi below.

Aerial and topside views show not only the erosion, but the leaking of sand into the deep currents.

Below the sea wall lies unimaginable damage to the island’s natural barrier.

Ricky worries about the long-term repercussions of the damage to the reef.

“These changes are a debt we can never afford to repay to our environment - a debt that grows heavier and more impossible with each passing day.”